1. Origins

Environmental history is a rather new discipline that came into being during the 1960’s and 1970’s. It was a direct consequence of the growing awareness of worldwide environmental problems such as pollution of water and air by pesticides, depletion of the ozone layer and the enhanced greenhouse effect caused by human activity. In this development historians started to look for the origins of the contemporary problems, drawing upon the knowledge of a whole field of scientific disciplines and specialisms which had been developed during the preceding century (Thoen 1996: 1; Worster 1988: 190; Verstegen & van Zanden 1993: 11). We can distinguish two important 19th century origins of environmental history: ecology and geography. In modern environmental history, ecological concepts are used to analyse past environments and geography used to study the ever-changing face of the earth. The surface of the earth is constantly changing and reshaping under geological, climatic, biological and human forces. At the beginning of the twentieth century geographers stressed the influence of the physical environment on the development of human society. The idea of the impact of the physical environment on civilisations was first adapted by historians of the Annales school to describe the long term developments that shape human history (Bramwell 1989: 40-41; Worster 1988: 306; Burke 1991: 14-15).

Two other roots of environmental history are the archaeology and anthropology of which the latter introduced ecology into the human sciences. The emergence of world history, with works by McNeill and Thomas (McNeill: 1967; Thomas 1956) among others, introduced interdisciplinary and continental wide, even world scale studies into history. Ecology and the interdisciplinary method became later two important features of environmental history (Thoen 1996: 2).

These were the foundations on which environmental history was founded in the 1960’s. Rodrick Nash coined the term environmental history in an article about the impact of past human societies on the environment published in the Pacific Historical Review in 19721. Nash’s writings were initially unilateral: he studied the impact of human society on the natural environment. Thanks to the work of Worster, Pfister, Brimblecombe, Ponting and others, environmental history became matured, what means less unilateral and influenced by political motives (Worster, 1988; Pfister & Brimblecombe, 1992; Ponting, 1991). At the present day environmental history is an international and interdisciplinary undertaking.

2. What is environmental history?

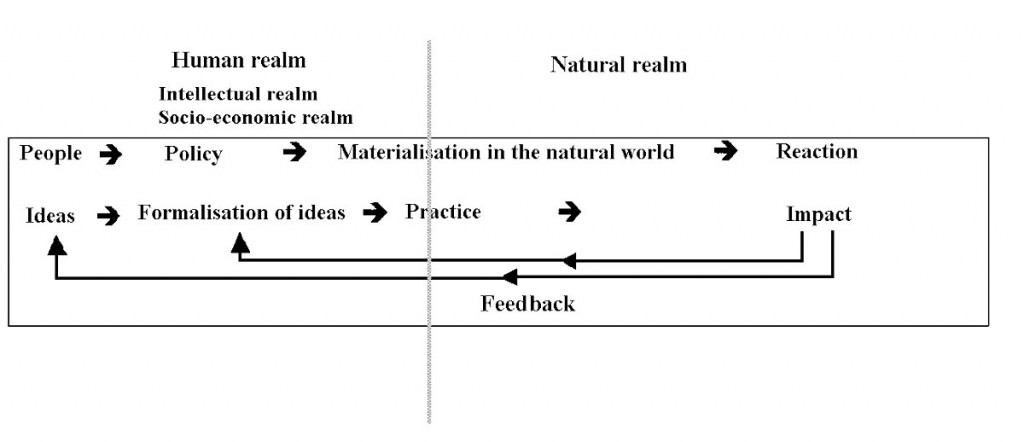

Environmental history is always about human interaction with the natural world or, to put it in another way, it studies the interaction between culture and nature. The principal goal of environmental history is to deepen our understanding of how humans has been affected by the natural environment in the past and also how they have affected that environment and with what results. This is called the bilateral approach of environmental history (Smout 1993: xiii.; Verstegen & van Zanden 1993: 11). The most common definition of environmental history is as follows: environmental history is studying the interaction between humans and the environment in the past. To study the relationships between humans and the surrounding world, we must try to understand how the interaction between the two works.

Donald Worster has recognised three clusters of issues to be addressed by environmental historians (1988: 289-308). The first cluster deals with the human intellectual realm consisting of perceptions, ethics, laws, myth and the other mental constructions related to the natural world. Ideas about the world around us influence the way we deal with the natural environment. Here we enter the second level of issues to be studied: the level of the socio-economic realm. Ideas have an impact on politics, policies and the economy through which ideas materialise in the natural world.

But the world is not static, so it reacts on our actions to influence the material world. With the impact of human actions the natural world we enter the third level of environmental history. This level deals with understanding nature itself, the natural realm. In the case of woodland history it is the way forest ecosystems have been working in the past and how they were changed by human actions. The impact of human actions on the natural world is causing a feedback that changes our ideas, policies, economy etc. In this way the natural world defines the limits of what we can do, and what not. Within this framework we try to change reactions we do not like and continue practices which, in our view, are successful. This model of the interaction between man and the environment depicts the concept of the separation between humans and nature. Although this division between the human and the natural realms is an artificial one, it can be a useful tool for the environmental historian in identifying important questions, the sources that might be able to answer the questions and the methods used to study these sources.

The fields of study in environmental history includes analysis of data on tides, winds, ocean currents, the position of continents in relation to each other and geology and includes the history of climate and weather and the pattern of diseases. Environmental history is also the story of human exploitation of the natural world. It is about the impact of agriculture on soil and landscape, the history of forests, the effects of hunting and grazing; but also about the environmental impact of mining, transportation, urbanisation and industrialisation. And last, but not least, environmental history is about unmasking myths and distorted perceptions of the past. Myths and false perceptions are not based on historical facts and can be highly influential, even in government en scientific circles. It is an important task of environmental history to correct these misconceptions of the past. It can help to understand our current problems better and to make proper decisions to deal with these problems, now and in the future (Smout 1993: xiii-xv).

3. The historian and environmental history

Environmental history is an interdisciplinary subject. That means that historians, scientists and other scholars must look over the boundaries of their own subject. The historian must be aware that he or she sometimes needs to apply some principles from the natural sciences, such as ecology, biology and forestry, to understand what happened in the past. However, this does not mean that the historian must become a scientist. He is and remains an historian with the task to master and understand the past as a key to a better understanding of the present. But to do so he or she must look over the boundaries of history and even the humanities and acquaint themselves with the nomenclature and principles of other disciplines, especially the natural sciences. This does not mean that they have to become experts in these fields, but to use it as a tool to get a better understanding of historical problems.

However, the contemporary valuation of environmental criteria is different from those used in the past. To analyse the impact of human action on the natural world in the past and the changes caused by this, a historian must use the modern principles of ecology and the environmental sciences. But this poses a threat to the way we interpret and value the past because notions as sustainability, equilibrium systems, biodiversity etc. are modern notions. Environmental historians, like any historian, must be aware that the present and its problems influence how we perceive the past. The historian is a product of his own age, and bound to it by the conditions of the times in which he lives. This can lead to a distorted or even false vision of the past. Therefore we must recognise the historically defined character of the values and ideas in our sources. We must try to prevent ourselves from projecting our contemporary ideas and values on the past (Carr 1991: 21-24). It is to others to judge the actions of people in the past and try to learn from it.

4. Environmental history today

During the last 40 years environmental history grew from an interest of some historians and natural scientists into a full-fledged academic discipline. In the United States environmental history gained a firm institutionalised base which is reflected in the fact that the annual meetings of the American Society for Environmental History, established in 1975, attracts over 500 participants. Environmental historical research in Europe is fragmented due to different academic cultures, multiple languages and funding models. However, since the 1980s there have been very promising and successful initiatives, both on the national and pan-European level. In 1986, the Dutch foundation for the history of environment and hygiene Net Werk was founded. One of the most important goals of this foundation was to improve the communication between Dutch researchers with an interest in environmental history. Up to the early 2000s the foundation used to publish four newsletters per year.

Since 1995, the White Horse Press in Cambridge (UK) is publishing a journal with the title Environment and History. As an interdisciplinary journal, Environment and History aims to bring scholars in the humanities and biological sciences closer together in constructing long and well-founded perspectives on present day environmental problems. The same can be said for the Tijdschrift voor Ecologische Geschiedenis (Journal for Environmental History), a combined Flemish- Dutch initiative published by the Academia Press in Gent, Belgium. This journal is mainly dealing with topics in the Netherlands and Belgium but it also has an interest in European environmental history. Each issue contains abstracts in English, French and German. In 1999 the Journal was changed into a yearbook for environmental eistory and since then every year a volume has been published until 2013. In late 2014 the Jaarboek was succeeded by a new open access Journal: The Journal for the History of Environment and Society (JHES).

The oldest Institute for Environmental History in Europe is based at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. This institute plays an important role in co-ordinating research in Scotland and since its establishment in 1991, the Institute organised several conferences on woodland and environmental history. The purpose of the first conference in December 1992 was to demonstrate the breath and vitality of environmental history in Scotland. One of the spearheads of research in Scotland is woodland history. With this knowledge it is not surprising that the second conference held in April 1995 was on Scottish woodland history. Both conferences resulted in the publication of two books containing papers presented during the conferences.

In the past 20 years there have been similar initiatives in other European countries. One of the difficulties is the language barrier that prevents historians from looking for environmental history books and journals in other European languages than their own or in English. In April 1999 a meeting was held in Germany to overcome these problems and to co-ordinate environmental history in Europe. This meeting resulted in the creation of the European Society for Environmental History (ESEH). Only two years after it was established, ESEH held its first international conference in St. Andrews, Scotland. Around 120 scholars attended the meeting and 105 papers were presented on topics covering the whole spectrum of environmental history. The conference showed that Environmental History is a viable and lively field in Europe and since then ESEH has expanded to over 400 members and continues to grow. Since the inaugural conference in St Andrews ESEH has organised bi-annual international conferences attracting increasing numbers of scholars in 2003 and 2005, 2007, 2011, 2013 and in 2015.

Also important for the further development of environmental history in Europe is an increased institutionalised base at University level. In 1999 the Centre for Environmental History was established at the University of Stirling. Today it continues as the Centre for Environment, Heritage and Policy (CEHP). The Centre is mainly a research institute, but also organises seminars and offers postgraduate training. In addition some history departments at European universities are now offering introductory courses in environmental history.

A very significant development and broadening of the field was the creation of the Rachel Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society (RCC) in 2009. The RCC is a joint initiative of Munich’s Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and the Deutsches Museum. The initial focus was on environmental history but at present the RCC is a research institution for the environmental humanities. This wider focus of the centre makes sense since it puts environmental history in its rightful wider context and allows for making links to other research areas and expertise. The activities of the RCC is diverse and includes a fellowship program, publishes a journal and book series, hosts a portal for digital resources, and organizes conferences and workshops. Its goal is to widen the debate about human societies and the environment and to include perspectives from the humanities. This means involving historians, anthropologists, social scientists, theologians, cultural and media specialist and many other disciplines. It also strives to build bridges to the natural sciences and to provide these scientists with unique insights from the humanities by looking at the problems and solutions that our global society has faced in the past as well as now. The RCC has quickly become the centre for scholars active in environmental history and the environmental humanities and is part of a worldwide research network.

Besides widening the institutional base, environmental history has also become a increasingly global undertaking with the creation of new societies and network. In 2004, the Latina American and Caribbean Society for Environmental History (Sociedad Latinoamericana y Caribeña de Historia Ambiental in Spanish and SOLCHA for short) was established. Latin America has a rich tradition in the study of environmental history but this is not often recognised as such because it is undertaken in a multitude of disciplines. The objective of SOLCHA is to overcome this problem and to encourage research, the debate of ideas, and to promote education in the field of Latin American and Caribbean Environmental History, through an interdisciplinary perspective. SOLCHA aims to stimulate the contact among researchers who adopt the historical perspective that includes the environment.

Environmental history is also developing strong roots in Asia, not in the least in China. In order to increase the profile of East Asian Environmental History and to improve communication between researchers world wide the Association for East Asian Environmental History (AEAEH) was created in 2009. So far AEAEH has held two bi-annual conferences, in 2011 and 2013, that attracted an increasing number of scholars and that is set to be repeated at their conference in 2015.

Environmental History in Australasia is less formal organised but since 1997 the research community in this part of the world is bound together trough the informal Australian and New Zealand Environmental History Network. The Network is an initiative of the Centre for Environmental History at the Australian National University and aims to “provide a means to communicate with each other and exchange information about forthcoming events and new publications in Australia and New Zealand”. The Network centres upon a web portal with links to organisations in Australia and New Zealand with interests in environmental history, and to provide a one stop shop to Australia for international groups with interests in global environmental history. Because of the large size and relatively small populations of Australia and New Zealand this web-based informal network is well suited to environmental history researchers and organisations in this part of the world.

The internationalisation and institutional recognition of environmental history continues, although it is becoming increasingly part of the emerging environmental humanities. This is also visible at the attendance of the Wold Congress of Environmental History, that is held every five years. This large international meeting is not only attracting humanists and social scientists but also scholars from any other humanities subject imaginable as well as scientists from the natural sciences. This development of expansion and broadening has gone with fits and starts and the future of the field looks bright, particularly if environmental historians embrace the emergence of the environmental humanities as an umbrella field.

Notes and bibliography

1 Rodrick Nash published in 1967 Wilderness and the American Mind. In 1972 he introduced the term “environmental history” in an article in the Pacific Historical Review.

—————————

Bramwell, Anna 1989: Ecology in the 20th Century, a History (New Haven).

Brimblecombe, P and Pfister, C (eds), 1990: The Silent Countdown: Essays in European Environmental History(Berlin).

Burke, Peter 1990: The French Historical Revolution. The Annales School, 1929-89 (Oxford).

Carr, E.H. 1991: What is History? (Harmondsworth).

McNeill, William H. 1976: Plagues and Peoples (New York).

Ponting, Clive 1991: A Green History of the World (London).

Smout, T.C. (Ed.) 1993: Scotland Since Prehistory. Natural change & Human Impact (Aberdeen).

Thoen, Erik 1996: ‘Editoriaal’, In: Tijdschrift voor Eologische Geschiedenis, p. 1.

Thomas, William L. 1956: Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth (Chicago, London).

Verstegen, S.W. & van Zanden, J.L. 1993: Groene Geschiedenis van Nederland (Utrecht).

Winiwarter, Verena (ed.), ‘Environmental History in Europe from 1994 to 2004: Enthusiasm and Consolidation’,Environment and History, 10(2004): 501-530.

Worster, Donald 1988: The ends of the earth. Perspectives on Modern Environmental History (Cambridge).

Recent Comments