Historically, forests in Scotland contributed in a variety of significant ways to the welfare and needs of rural communities. During the 20th century, forestry moved away from forestry for local use in favour of large-scale production forestry for distant markets. However, since the 1980s more emphasis is placed on nature conservation, recreation, as well as fulfilling local economic demands. This pattern of changing rural land-use has produced a new type of forest owners: rural communities. The aim of this short essay is to chart the developments that gave rise to community forests in Scotland.

Forestry policy 1919-1980

By the turn of the 20th century only 5 per cent of Britain supported forests and woodland, and the limited timber reserves were severely depleted during the submarine blockade of the Great War (1914-1918). The Forestry Commission (FC) was formed in 1919 in response to a need to establish a strategic reserve of timber in the UK. In 1957, in a world dominated by the spectre of nuclear warfare, it was decided that a policy of maintaining a strategic timber reserve had become obsolete. Other justifications such as social and economic objectives replaced strategic ones as the chief justification for the forestry policy. By the 1970s it had been demonstrated that afforestation for timber production was barely making a profit. It was at this time that recreation, conservation, landscape and rural employment were clearly accepted as policy objectives rather than as by-products of forestry.

The Flow Country debate

The Flow Country of Sutherland.

Photo: Geame Smith/Geograph.org.uk

During the early 1980s import saving was advanced as the principal justification for the continued expansion of forestry and new planting targets were announced. The private forestry sector was encouraged to take advantage of tax incentives and grants provided by the Treasury and administered by the FC to carry out afforestation schemes (Mackay 1995; Oosthoek 2001).

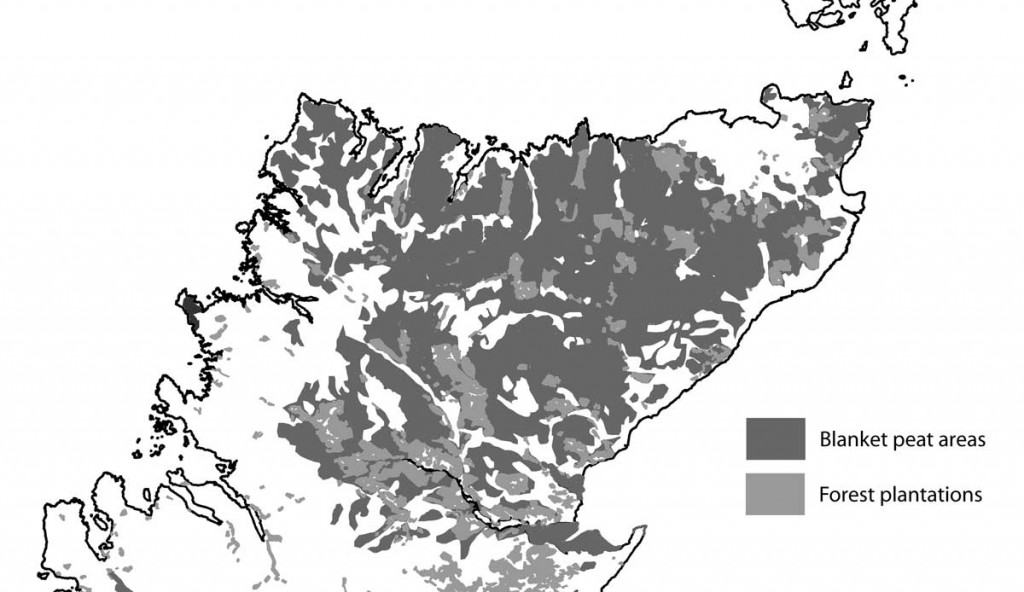

In 1985 the Nature Conservancy Council (NCC) published a report criticising forestry operations in the north of Scotland. The report drew attention to the extensive planting undertaken in the Flow Country of Caithness and Sutherland. The Flow Country is the largest continuous expanse in Britain of a type of peat moorland known as “blanket bog”, which has a unique ecology and landscape, and the creation of massive conifer plantations threatened to destroy it. The Forestry operations were made possible through the massive tax reductions available for forestry in remote rural areas. Not long after the NCC report the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) started a public campaign against forestry in the Flow Country (Mackay 1995).

The campaign had a profound impact on both public opinion and the FC. The dislike of conifers by the general public was increased to an unprecedented degree but was ignored by both the Commission and private forestry sector. However, in March 1988, without any warning, the tax incentives for forestry were removed. The FC was shaken by this fiscal change and commented in its annual report that it needed “a period of adjustment” (Forestry Commission 1988). During this period of adjustment the FC continued to sell off significant parts of its forestry estates to the private sector. This disposal programme was initiated under the Conservative Government as part of its privatisation policy in the early 1980s (Jeanrenaud & Jeanrenaud 1997). The sell-off programme of the FC was mainly aimed at the commercial forestry sector, but in 1987 a new group of unexpected buyers of FC estates emerged: local communities.

The first community forest

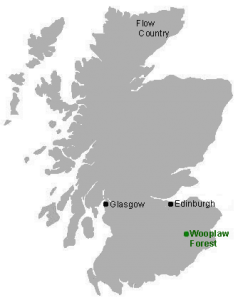

Map of Scotland showing locations of

the Flow Country and one of the first

community forests in Scotland

In 1987 the first Scottish Community forest was established with the acquisition of Wooplaw forest in the Scottish Borders. The project originated in 1985 with Tim Stead, a wood sculptor, who worked and lived in the Scottish Borders. For aesthetic reasons he had decided to use only native British timber and this led on to the idea of restoring this resource as well as use it. He came up with the idea of ‘axes for trees’ and produced hundreds of handmade hardwood axe heads, which he sold to raise money to buy a piece of land on which native trees could be planted.

The publicity for this scheme drew the attention of two people involved in the native woods movement in Scotland, Donald McPhillimy and Alan Drever. They met with Tim Stead in 1987 and together discussed the possibility of creating a community woodland. This led to the formation of Borders Community Woodlands (BCW) to take the project forward and a large public meeting was held in Melrose. At almost the same time, Wooplaw, a local 23ha woodland, came on the market and within 3 months BCW had succeeded in securing sufficient funds to purchase the first community woodland of its type in the UK (Forestry Commission Website).

Forestry Commission and NGOs

The Forestry Commission realised that community forests provided a suitable tool to polish up its damaged image. In 1989 it launched a community forest initiative of which the Central Scotland Forest was a pioneer example. This project was designed to transform much landscape between Glasgow and Edinburgh into a complex of productive and amenity forests (Mackay, 1995). The Central Scotland Forest was a successful showcase but the Commission was reluctant to make this kind of forestry an integral part of its policy.

In 1995, three Scottish non-governmental organisations (NGOs), The Highland and Islands Forum, Reforesting Scotland and the Rural Forum Scotland initiated the Scottish Rural Development Forestry Program (SRDFP). The main aim of this programme was “… to enable local individuals and groups to realise the potential of Forestry as a land-use with environmental, social and economic benefits” (SRDFP 1995). The three NGOs provided information and, to a lesser extent, financial support for setting up community forest groups. At the same time the FC announced its Community Woodland Supplement scheme to help local groups manage their own forests.

Success of the community forests

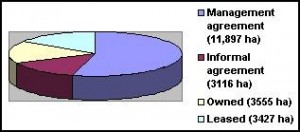

Area of woodland owned or managed by

community groups, ca 2001.

Source: Delivering the Scottish Forestry Strategy

Between 1997 and 2001 the number of community forest initiatives increased further to a total of 51 covering 22,000 hectares (Scottish Executive 2001). Some of these initiatives were based on the desire to manage the forests in a more holistic way, with greater emphasis on conservation and biodiversity. However, the majority of new schemes have been motivated by the aspiration of rural communities to enhance the contribution of local forests to local livelihoods. It was especially felt that local State-owned plantations should contribute to the local economy. The Forestry Commission responded positively to this challenge and launched a new community engagement policy for Scotland in July, 1999. Although the total area of community-managed forests remains small in comparison to State-owned forests, it is perhaps the beginning of a return of forestry for the welfare and needs of rural communities.

Note: Read more about community forests and the Flow Country debate in: K. Jan Oosthoek, Conquering the Highlands. A history of the afforestation of the Scottish Uplands (Canberra: ANU Press, 2013), Chapter 9.

References

FORESTRY COMMISSION (1988): Annual Report and Accounts 1987-88. FC: Edinburgh.

INGLIS, A.S. (1999). “Implications of devolution for participatory forestry in Scotland&. Unasylva Vol 50(1999): 45-51.

JEANRENAUD, Sally & JEANRENAUD, Jean-Paul (1997). Thinking Politically about Community Forestry and Biodiversity: Insider-driven initiatives in Scotland. WWF-International: Gland.

MACKAY, DONALD (1995). Scotlands’s Rural Land Use Agencies. Scottish Cultural Press: Aberdeen.

OOSTHOEK, K.J.W. (2001). An Environmental History of State Forestry in Scotland, 1919-1970. PhD thesis, Stirling.

RYLE, G.B. (1969). Forest Service. The First Forty-five Years of the Forestry Commission of Great Britain. David & Charles: New Abbot.

SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE (2001). Delivering the Scottish Forestry Strategy. Forestry Commission: Edinburgh.

SRDFP (1995). Phase One Report. Highlands and Islands Forum: Inverness.

FORESTRY COMMISSION WEBSITE: Rural development forestry: summary of case studies. http://www.forestry.gov.uk/website/pdf.nsf/pdf/toolbox.pdf/$FILE/toolbox.pdf Accessed: 20 July 2003.

This essay was presented as a poster at the 2nd conference of the European Society for Environmental History in Prague, August 2003.

Recent Comments