By Fred Milton

The late Victorian era saw an increased public concern for the welfare and protection of wildlife, particularly birds. This included the formation of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), the institution of bird protection legislation and the founding of children’s societies with the objective of educating and teaching children to be kind to wildlife. This relationship between children and their behaviour towards animals was of course not new. John Locke warned in 1693:

One thing I have frequently observed in children, that when they have got possession of any poor creature, they are apt to use it ill: they often torment and treat very roughly young birds, butterflies and other poor animals… with a seeming kind of pleasure. This I think should be watched in them… they who delight in the suffering and destruction of inferior creatures, will not be apt to be very compassionate or benign to those of their own kind…’

William Hogarth then graphically illustrated the fate of children who abused wildlife in his Four Stages of Cruelty pictures of 1751, when his subject Tom Nero moves from torturing animals as a child to murdering his mistress as an adult.

This perceived danger was then a subject that constantly taxed the Royal Society for the Protection for Animals (RSPCA) who called for literature to combat this perceived danger. Whilst appropriate reading material was produced in abundance, little practical action was taken until the 1870s, when two movements began that actively recruited children to promise to undertake a ‘pledge’ that they would be kind to birds and animals. One of these societies was the Band of Mercy that developed out of the temperance movement in 1875 and fell under the auspices of the RSPCA in 1883. By 1889 there were 113,000 children assigned to 540 Mercy Bands in Britain. This initiative spread also worldwide and 7,344 bands were formed in the Empire and North America serving 600,000 children.

Parallel to this movement was the initiation of children’s societies in the provincial newspaper press that had similar objectives to the Band of Mercy. The first of these ‘press societies’ was the Dicky Bird Society (DBS) launched by the editor of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, William Adams in 1876. Under the pseudonym of Uncle Toby, the DBS actively enrolled members from not just Tyneside but across the world and by 1900 300,000 members had taken the following pledge:

I hereby promise to be kind to all living this, to protect them to the utmost of my power, to feed the birds in the winter time, and never to take or destroy a nest. I also promise to get as many boys and girls as possible to join the Dicky Bird Society.

The DBS repeatedly encouraged its members to provide food for the birds. It actively suppressed egg collecting, campaigned against the feather millinery trade and highlighted the cruel sport of live pigeon and sparrow target shooting. This was all done with the active contribution of its child members who wrote hundreds of letters each week to the society’s column in the Weekly Chronicle, put up bird boxes in their gardens and parks, and attended marches and parades to celebrate the society’s milestones. When 100,000 members were recruited in 1886 two parades were held in Newcastle city centre and a theatre show was put on to entertain 8,000 children. On reaching 250,000 members in 1894 upwards of 40,000 children attended a celebratory day’s event in Newcastle. It was not just children who were attracted to the Dicky Bird cause, Adams persuaded public figures such as Lord Tennyson, Florence Nightingale and Baden Powell to lend their esteemed names to his society as honorary members.

Other provincial newspapers and children’s magazines closely monitored this success and a host of facsimile press societies sprung up across Britain. None quite matched the success of the DBS, but nevertheless the membership of four other societies broke through the 100,000 barrier. A total of 36 newspaper titles hosted societies for their young readers, and they could be found in most major cities in Britain. These societies were not the preserve of the middle or upper class children. Whilst junior members of the Royal Family joined the Humane Society of the children’s magazine Little Folks, the DBS received regular correspondence from workhouse children, who wrote to Uncle Toby telling him how they saved their crumbs from their lunch to ‘feed the dickies’.

Calculating the membership of these societies is difficult as not all of the newspapers printed a membership list. However an estimate of 1.1 million children is not unreasonable, although it must be stressed that membership lists merely counted children who had taken the ‘pledge’ and were not adjusted to take into account those who died or recanted their promises. Nevertheless the sheer number of children involved and their contribution to bird conservation must be regarded as highly significant. This constitutes the rationale for undertaking this thesis. Very little academic research has been undertaken on this strand of children’s movement, and whilst histories of the Band of Mercy have been produced, they are dated, largely approving and in need of a fresh critique.

The Victorian newspaper press has been well researched, but analysis tends to focus upon primarily to its political commentary and ownership rather than content. This deficiency has been recognised and led to recent calls, notably by Graham Law, for detailed scrutiny of the provincial press. With the exception of the Daily Mirror and Daily Mail and some of the political and religious press, all of the nature societies and children’s can be found in provincial newspapers. Notably there is a heavy bias towards northern England. This ‘clustering’ may have been because these societies and columns were key commercial features of the newspapers and rival publications simply had to introduce these features for fear of loosing readership and thus valuable advertising revenue.

The children’s magazine and periodical press has also been subject to widespread scrutiny, but there appears little study of the linkage between the periodical press and children’s newspaper columns. The growth of the some of the periodical press, notably the Boy’s Own Paper, has been seen as the result of the publication ‘war’ against the ‘penny dreadful’ press that was thought to pollute young minds and lead children to torture animals and birds. The newspaper societies naturally produced wholesome reading and the Band of Mercy commonly warned their readers to avoid the ‘forbidden fruit’ of insidious reading material. Therefore these societies must have been useful tools in the battle to keep children away from illicit reading material. Similarly all of these societies offered regularly letter writing and essay competitions. For instance the Dicky Bird Society’s members were encouraged to write essays, whose discussion subjects included ‘Bird Millinery – Why we Should Oppose It’ and ‘The Cowardice of Cruelty’. School logbook evidence also illustrates how children, in the absence of text books, read newspapers at school and undertook pledges to promise to be kind to birds and animals at school. The RSPCA had long used essay competitions to spread its message, and by 1909 over 300,000 essays were received each year from London schools in their annual essay competitions. Therefore it can been confidently concluded that the children’s nature societies must have played a significant role in educating children not just about the need to be benevolent towards wildlife, but also assisted in increasing literacy levels.

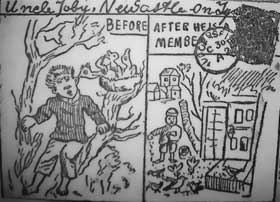

It is very clear from the inference of this

illustrated envelope of what the members

thought were the real achievements of the

DBS as the boy is turned from egg collector

to bird feeder by taking his pledge for the DBS.

Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, 4 February 1888

However not all children were enthusiastic in joining the nature societies, particularly boys. Evidence suggests that some thought that these movements had ‘baby’ names and were frightened that should they join their names would be made public in the newspaper and they would be made fun of by their peers. A key part of this reluctance was the contemporary opinion that boys had to be ‘manly’ and joining these nature societies definitely not regarded as a trait of sturdy ‘manliness’. However the nature societies worked hard to redefine ‘benevolence’ as a key characteristic of manliness in order to enlist working boys when other contemporary youth movements reiterated that boys had to be sturdy and heroic and any derivation from this was met with accusations of weakness and femininity. For instance the leader of the Dundee Sunbeam Club stressed to his members that they should not be ashamed at defending birds and instead it was egg collectors who were the real cowards for torturing birds. A gender analysis of Dicky Bird Society membership illustrates that these societies were successful in persuading boys to join, as just over 50% of new members in February 1880 were male. However we must remember that male literacy rates were higher than females and this may account for the gender parity in membership rates. Nevertheless the fact that over 1.1 million children ascribed themselves to these movements is clear evidence that the societies were successful in overcoming ‘manly’ objectives. This large number of children recruited must have a visible impact on bird conservation, particularly in the amount of birds that would have been saved by children providing food each winter and the decline in egg collecting and cruelty overall.

Existing studies of conservation movements have generally focused on the mainstream RSPB and RSPCA societies and their invariably upper class adult members. This study illustrates how the conservation movement was more far-reaching than previously recognised and how it placed great store on children’s education. Indeed to be truly successful the nature conservation movement of the late nineteenth century had to be inclusive by attracting all classes, including children.

Selected References

Ashton, Owen W., W.E. Adams – Chartist, radical and journalist (1832-1906), (Whitley Bay, Bewick Press, 1991).

Dixon, Diana, ‘Children’s Magazines and Science in the Nineteenth Century’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 34/3 (Fall 2001), pp. 228-238.

Dougherty, Robin W., Feather Fashions and Bird Preservation – A Study in Nature Protection, (Berkley, University of California Press, 1975).

Fairholme, Edward G., and Pain, Wellesley, A Century of Work for Animals. The History of the RSPCA 1824-1924, (London, John Murray, 1924).

Ferguson, Moira, Animal Advocacy and Englishwomen, 1780-1900. Patriots, Nation, and Empire, (University of Michigan, 1998).

Freeman, R.B. ‘Children’s Natural History Books before Queen Victoria’, History of Education Society Bulletin, 17(Spring 1976), pp. 7-21.

Harrison, B, ‘Religion and Recreation in Nineteenth-century England’ Past & Present, 38 (1967), pp. 98-125.

Harrison, B, ‘Animals and the State in Nineteenth Century England’, English Historical Review, 88 (1973), pp. 786-820.

Haynes, Alan, ‘Murderous Millinery’, History Today, 33/7 (July 1983), pp. 26-30.

Henderson, Tony, ‘The Lost Story of a Little Dicky Bird’, Newcastle Journal, 1 February 2003, pp. 68-69.

Kean, Hilda, Animal Rights. Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800, (London, Reaktion Books Ltd., 1998).

Jenkins, E. W., ‘Science, Sentimentalism or Social Control? The Nature Study Movement in England and Wales, 1899-1914’, History of Education 10/1 (1981), pp. 33-43.

Law, Graham, ‘Before Tollotsons: Novels in British Provincial Newspaper, 1855-1873’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 32/1 (Spring 1999), pp. 43-79.

Leslie, W. Bruce, ‘Creating a Socialist Scout Movement: The Woodcraft Folk, 1924-42’, History of Education, 13/4 (1984), pp. 299-311.

MacKenzie, John M., ‘Hunting and the Natural World in Juvenile Literature’, in Imperialism and Juvenile Literature, ed. Jeffrey Richards, (Manchester, Manchester University Press, c.1989).

Moore-Colyer, R. J., ‘Feathered Women and Persecuted Birds; The Struggle Against the Plumage Trade c. 1860-1922’, Rural History, 11/1 (2000), pp. 57-73.

Moss, Arthur W., Valiant Crusade: The History of the RSPCA, (London, Cassell, 1961).

Noakes, Richard, ‘The Boy’s Own Paper and the late-Victorian juvenile magazine’, in Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical. Reading the Magazine of Nature, eds. Geoffrey Cantor, Gowan Dawson, Graeme Gooday, Richard Noakes, Sally Shuttleworth and Jonathan R. Topham, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Ritvo, Harriet, The Animal Estate. The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian

Age, (London, Penguin, 1987).

Ritvo, Harriet, ‘Learning from Animals; Natural History for Children in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’, Children’s Literature, 13 (1985), pp. 72-93.

Shiman, Lilian Lewis, ‘The Band of Hope Movement: Respectable Recreation for Working Class Children’,Victorian Studies, 17/1 (1973), pp. 49-74.

Springhall, John, Youth, Empire and Society. British Youth Movements, 1883-1940, (London, Croom Helm, 1977).

Thompson, F.M.L, The Rise of Respectable Society – A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830-1900,(London, Fontana Press, 1988).

Turner, E. S., All Heaven in a Rage, (Fontwell, Centaur Press Ltd., 1992.).

Turner, James, Reckoning with the Beast – Animals, Pain and Humanity in the Victorian Mind, (Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1980).

Vance, Norman, ‘The Ideal of Manliness’ in The Victorian Public School. Studies in the Development of an Educational Institutions, eds. Brian Simon & Ian Bradley, (Dublin, Gill & Macmillan, 1975).

Vance, Norman, The Sinews of the Spirit. The Ideal of Christian Manliness in Victorian Literature and Religious Thought, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Dr Fred Milton is a scholar based at the University of Teeside. He is specialised in 19th century history of the press and nature conservation. Recently he completed a thesis that explores the development of children’s nature societies in late nineteenth century Britain. The abstract above gives an introduction to his work and the rationale for this work. You can contact Fred at F.S.Milton@ncl.ac.uk.

Listen to Fred Milton talking about the DBS on the Exploring Environmental History Podcast.

Recent Comments